Riding through the countryside of Laos’ remote Xieng Khouang province, we spied verdant rolling hills, villagers of all ages escorting livestock on the dusty roadside, and giant craters disfiguring the landscape. For an instant, these cavities in the red earth evoked images of sand traps on golf courses. However, with Laos’ tragic distinction of being the world’s most bombed country per capita, not much golf is being played here.

Guided by a local father-and-son team, we had embarked on a day trip to visit the country’s mysterious archaeological treasure: the Plain of Jars. We would also visit two villages: Ban Naphia and Ban Tajok, nicknamed ‘Spoon Village’ and ‘Bomb Village,’ respectively.

Before we could continue, however, we would have to wait until a temporary roadblock was cleared. A Laotian man with a grey megaphone in hand motioned for our vehicle to stop. Our guides explained that it was a safety measure, as the man’s teammates working out in the nearby countryside had likely encountered a piece of unexploded ordnance (UXO).

About a minute passed, then we heard a thunderous explosion in the distance. As the rumbling noise settled, and the area’s serene soundtrack returned, we were told the good news: a piece of UXO had just been successfully destroyed. The man on the roadside ushered our driver to proceed, and as our van rumbled ahead, the dirt road’s red dust danced in the air. Everyone in the van was quiet. I had goosebumps, thinking about the triumph of that moment, contrasted with all the tragic accidents that had come before it.

A History of War, Hope for the Future

From 1964-1973, it is estimated that American military forces dropped more than two million tons of bombs on Laos – even eclipsing those dropped on Germany and Japan during World War II. For nine years, bombs rained down on Laos every eight minutes. The United States Air Force flew almost 600,000 bombing missions over Laos. (This one and a half minute video shows the extent of the bombings, with each dot symbolizing a bombing run.)

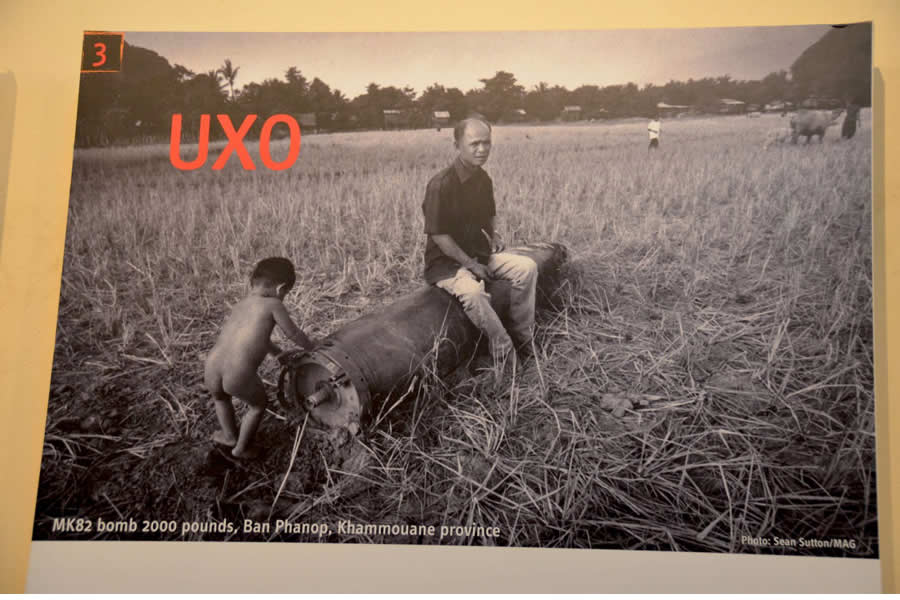

Thirty percent of the cluster munitions used (also known as ‘bombies’), failed to detonate. Tragically, it is often Laos’ youngest and poorest citizens who are still killed and maimed today when coming into contact with this UXO. Accidents also occur as citizens try to ready land for farming. Scrap-dealers, trying to make a living from the plethora of war scrap are also at risk. So too are children, attracted by the shiny, metallic appearance of the bombs. According to the book, Eternal Harvest: The Legacy of American Bombs in Laos, there have been 20,000 deaths and injuries since the end of the Vietnam War. As we would learn, there are many dedicated people and organizations working in Laos trying to make all the country’s land safe again.

From Bombs to Fences, Flower Pots & Spoons

It’s estimated that 60% of the Laotian population lives on less than $2 USD/day. With that statistic in mind, one can imagine why the prospect of war scrap collection can be appealing. Resourceful Laotians gather it either to swap it for cash, or repurpose it into utilitarian items such as herb planters, animal troughs, fences – even supports for stilted homes.

Perhaps the most unique use for war scrap that we’d see was as material for spoons, bracelets, and decorative charms. In the so-called ‘Spoon Village,’ we watched as a good-natured Laotian man extracted metallic liquid originating from a melted bomb tail, poured it into a wooden mold, let it harden and cool, and then unveiled a glimmering spoon. At the end of the visit, we swapped a handful of Laotian Kip (the equivalent of a few U.S. Dollars) for a trio of these homemade spoons.

We were reassured to learn that an organization had tested the metals for safety, not because we’d planned to eat with the spoons, rather because we were concerned about the man who works with the molten metal on a daily basis. Apparently, the agency’s tests showed that it was not harmful. Additionally, we heard that the war scrap used for the spoons had not been collected by an independent war scrap collector who could be putting himself at risk; instead, it had been given to the Spoon Villagers by organizations after it had been disarmed.

(Update: Despite the reassurance we were given, it’s important to note that the practice of transforming bomb scrap metal into other items is controversial. Several organizations, such as the Lone Buffalo Foundation, instead encourage a policy of Haam Jaap (don’t touch). This UXO awareness video, produced by Lone Buffalo students, highlights these dangers.

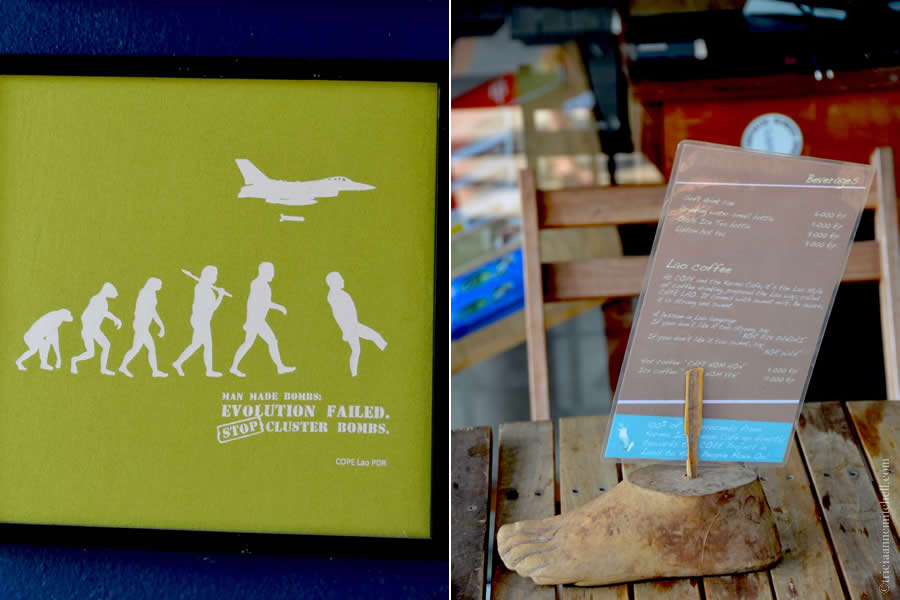

Via email, Lone Buffalo founder Mark Steadman elaborated on this issue. “Our view reflects that of COPE and the UNDP that putting value on war scrap could send out a dangerous message to those not educated in UXO awareness.”

Shawn and I didn’t know about Lone Buffalo when we visited Laos, however, you can learn more about this worthy organization in this NPR article.)

The Intriguing Plain of Jars

Situated in a remote region of Laos and eclipsed by enchanting Luang Prabang’s gleaming temples, the Plain of Jars are often regrettably left off of one’s list of places to explore while in Laos. The fields on which the jars are strewn are challenging to access by land, given Laos’ poor, mountainous roadways. And, to make matters worse for those in this region so hungry for tourism, Xieng Khouang was one of the worst-hit provinces during the so-called American ‘secret war’ in the country.

Instead of arriving via the Phonsavan Airport as many visitors do, we came overland via a remote and mountainous Vietnamese / Laotian land crossing. Welcomed into Laos with heartily spoken ‘sabaidees,’ our route from the border to Phonsavan consisted of serpentine roadways framed by lush foliage, stunning views and steep drop-offs.

No one is certain why the megalithic jars – thousands of them – are scattered about the Laotian landscape on approximately 90 different sites. One legend is that they were made to brew rice wine to celebrate a triumph over barbaric leaders. More recent studies have concluded that they were burial urns. The jars are believed to date back to between 500 BC and 200 AD.

Only a handful of the 90 jar sites have been cleared of UXO, thanks to admirable clearing work completed by NGOs and their Laotian male and female employees. Some funding has been provided by international development agencies too.

***

While in the Phonsavan area, our guided day trip to the Plain of Jars and Spoon and Bomb Villages were coupled with independent excursions to the province’s former capital, UXO education centers, and even a morning spent shadowing a Japanese team training to clear UXO. These experiences filled us with the greatest respect for the resilient citizens of Laos and the fearless men and women working hard to rid it of UXO. In fact, our days spent in the quiet province of Xieng Khouang provided many of our Southeast Asian trip’s highlights.

To learn more about how to help make Laos free from UXO, and to see Shawn’s video, please continue to the bottom of this post.

Video of This Experience:

Where in the World?

Learning & Doing More:

- Several organizations work to help victims, and remove UXO from the landscape. COPE, for example, offers donors the chance to buy a prosthetic leg for $75 USD, even $10 developmental toys for children with disabilities. Or, for about $45 USD, the nonprofit organization, MAG, can clear 20 sq/m of land, making it safe for agricultural or community use.

- So far, more than 115 nations have signed the Convention on Cluster Munitions, an international treaty that addresses the harm caused to civilians by cluster bombs. In 2010, this Convention became binding international law. The United States, Israel, Russia, and China are among those countries that have not signed the Convention. The Cluster Munition Coalition is a global campaign aiming to eradicate cluster munitions.

Planning Pointers:

- The Plain of Jars are located in northeastern Laos. The town of Phonsavan, where we stayed, makes a good launching point for exploring the various Plain of Jars sites. Phonsavan has a bit of a wild west feel in that it’s somewhat remote, but there are good basic tourist services there including tour operators, guesthouses and restaurants (Laotian, Western, and even Indian food). The Mines Advisory Group (MAG), which does noble work around the world to clear landmines, has a visitor’s center in Phonsavan that is well worth a visit. There is also a UXO Survivor Information Center (just two buildings away from the MAG Visitor’s Center) which has informational films, as well as handicrafts to purchase. The proceeds go to help UXO survivors.

- To get to Phonsavan, we traveled from Vinh, Vietnam. An early-morning bus took us close to the Laotian border, then we hired a driver to take us to the border. From there, we walked into Laos, and had the fortune of meeting a travel agent who was shuttling another passenger to Phonsavan. We hear that many visitors to Phonsavan avoid the country’s infamous curvy roads, and instead fly into the nearby Xieng Khouang Airport. Buses also link Phonsavan to Luang Prabang, Vang Vieng, and the capital city, Vientiane.

- While in Vientiane, we found that a stop at the COPE Visitor Center was also a must to better understand the country’s battle with unexploded ordnance.

- There’s more to do in the Phonsavan area aside from the Plain of Jars and UXO-related sites. We enjoyed visiting Mulberries Organic Silk Farm, a weaving co-op in the town’s outskirts. On several occasions, we also strolled Phonsavan’s outdoor produce market. Vong, a friendly Laotian employee at our guesthouse, who happens to teach English on the side, also invited us to come to his classes one evening.

- See the Highlights of Xieng Khouang website for more details.

- Need more inspiration? This link contains an index of all my posts from Laos.

Photography & text © Tricia A. Mitchell. All Rights Reserved. The video was created by my husband, Shawn.

Leave a reply to Bama Cancel reply