In the vineyard-dressed landscape of the Langhe, in Italy’s Piedmont region, hillsides rise steeply on one side, then drop off more gradually on the other. The name ‘Langhe’ is believed to have Celtic roots, meaning ‘tongues of land,’ alluding to these steep hillsides, and the area’s raised valleys. Our host, Marco Scaglione, from Meet Piemonte, described it this way:

“The Langhe’s soil has more of a clay composition, whereas the neighboring Monferrato and Roero districts tend to be more sandy. Imagine if you dropped a handful of sand onto a table top; the sand would form into a cone of sorts — more rolling, more gradual. Clay, however, can be molded into more steep hillsides and valleys.”

Like the Roero and the Monferrato, the Langhe landscape is also inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List.

Barolo & Barbaresco, the ‘King & Queen’ Wines of the Langhe

Barolo and Barbaresco are the wines most famously produced in the Langhe. Both of these powerhouse reds are made with the Nebbiolo grape. However, despite that commonality, the wines have distinctly-different personalities and manners of production.

Barolo wine, for example, must spend two years in barrels and an additional year aging in the bottle, whereas Barbaresco must only spend one year in the barrel and one year in the bottle.

While Barbaresco wine can generally be enjoyed when it’s younger, it doesn’t tend to age as well as Barolo does. Barbaresco is also said to be lighter, and more feminine.

Tasting a Trio of Wine at the Montaribaldi Winery

Surrounded by a sea of vineyards resembling a natural amphitheater, the family-owned Montaribaldi Winery greets visitors with wooden barrels brimming with red begonias, a children’s playground, and a table shaded by a grapevine-covered pagoda.

Inside, we’d meet Antonella Rivetti, the daughter-in-law of Montaribaldi’s founders, Pino and Carla Taliano. On a tour that would take us through the fermentation room and cellar, Antonella and Marco walked us through the basics of what Montaribaldi does.

“Barbaresco wine is the queen while Barolo is the king,”Antonella said, with a smile, while pointing to a bust likeness of the so-called ‘father of Barbaresco,’ Domizio Cavazza.

“At first, Barbaresco was the poor brother of Barolo, but it got recognition thanks to Cavazza’s help,” she added.

Cavazza, it turns out, was a gifted agronomist, who not only established a winemaking school in nearby Alba, but who also co-founded a cooperative that produced the first Barbaresco wine in 1894.

Like Barbaresco’s founder before them, the Montaribaldi Winery family is also involved in their community. When the winery commemorated its 20th anniversary last year, the team decided to donate money to a charity benefitting children with special needs rather than have a lavish party.

As for its winemaking philosophy, Montaribaldi is not yet certified organic, but the winery is moving in that direction.

“It’s a process that takes a while,” said Antonella. “We do use some natural fertilizer from stables, and some stems are composted as fertilizer.”

Unlike Monferrato wine country, which we’d visited the day before, Antonella explained that Montaribaldi doesn’t remove the grass that grows around the base of their grapevines.

“The better you do in the vineyard, the less work there is after the harvest,” she said. “Instead of removing the grass, we just cut it short. The grass helps to absorb water, which in turn controls humidity. It also helps prevent landslides.”

The Barbaresco Tower’s Dazzling Views

“The cities of Alba and Asti were enemies for centuries,” Marco said, as we took in extraordinary views of the Langhe-Roero countryside from the medieval Barbaresco Tower.

“Because of this rivalry, Alba had this tower to watch out for Asti.”

Barbaresco’s 30-meter-tall brick tower had only months earlier been opened to the public, however, it’s been around since medieval times — perhaps as far back as the 12th century.

Today, Alba and Asti are no longer warring city-states, of course, but the two cities do maintain a friendly rivalry. For example, Alba annually holds a donkey Palio race that pokes fun at Asti’s much-revered horse race. The latter event dates back centuries.

From the Barbaresco Tower, we had gorgeous views of the surrounding wine country. We could see the Tanaro River (which divides the Langhe and Roero districts). Off in the distance we could also glimpse Alba. Unfortunately, a perpetual haze prevented us from seeing the majestic, snow-capped Alps that give the Piedmont region its name. Piedmont literally means ‘at the foot of the mountain’.

Once back on Barbaresco’s cobbled streets, Shawn, Marco, and I passed bicyclists enjoying an afternoon coffee at a café. We also spotted a church-turned-wine-shop and a man selling local products. I was delighted to make an edible purchase: a traditional Piemonte cake made of hazelnuts. The Torta Nocciola Piemonte was simply wrapped in brown paper and tied with a twine-like rope. We brought the cake back to Germany, where we dressed it up for my father’s birthday.

The Snail-Shaped Town of Serralunga d’Alba

Motoring through the backroads of the Langhe, Shawn, Marco, and I embarked on a discussion of Italian misconceptions. Marco was passionate about the topic.

“In Italy, there is really no such thing as Alfredo sauce, or Chicken Parmesan. Spaghetti & Meatballs are also more of an Italian-American invention. Immigrants wanted to show their new social status and the fact they could afford meat, and thus the dish was born,” Marco said

Marco then asked me what international chain I hadn’t noticed in Italy. Shawn and I rarely frequent fast-food chains, so Marco caught me without a response.

“Starbucks, of course! In Italy, it’s customary to stand at a counter for a quick drink. You don’t see Italians commuting with coffee cups in hand, as you might elsewhere in the world.”

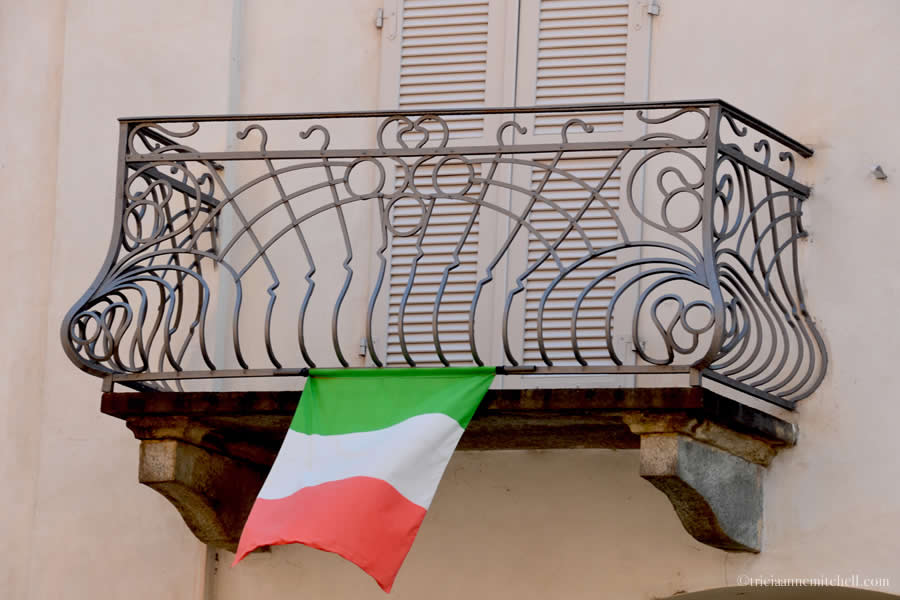

Our mini misconception lesson complete, we’d arrived in Serralunga d’Alba. The town’s nucleus is its fortress, from which businesses and homes spiral out in a snail-like pattern. Unlike Alba and Barolo, which seem to be more on the tourist radar, Serralunga d’Alba was rather quiet. A female resident read a newspaper on a bench, laundry hung from upstairs balconies, and we passed empty streets. No doubt, much of the town’s residents were enjoying the afternoon siesta or riposo. After our wine tasting, and the day’s whirlwind four cities’ tour, I felt as though I could join them in that endeavor!

Barolo Town, ‘The King’s’ Namesake

As we approached the world-famous town of Barolo, Marco mentioned that Barolo wine had actually been fine-tuned by a French woman named Juliette Colbert, from Bordeaux. Juliette married the prominent Marquis of Barolo, Carlo Tancredi Falletti, in the early 19th century. The pair’s coat of arms is still visible on Barolo’s castle. Today it houses a wine museum.

Juliette is said to have implemented Bordeaux-style wine-growing techniques in Piedmont. In addition to her oenological know-how, Juliette is also remembered for advancing various women’s and children’s causes. She also established a foundation for women and children that still exists today.

Elegant Alba, Home of Chocolate, Truffles & Wine

Though we witnessed a mock truffle hunt the day before in Monferrato, we would miss Alba’s famed White Truffle Fair by just a few weeks. There, prized fungi can fetch thousands of euros per kilo!

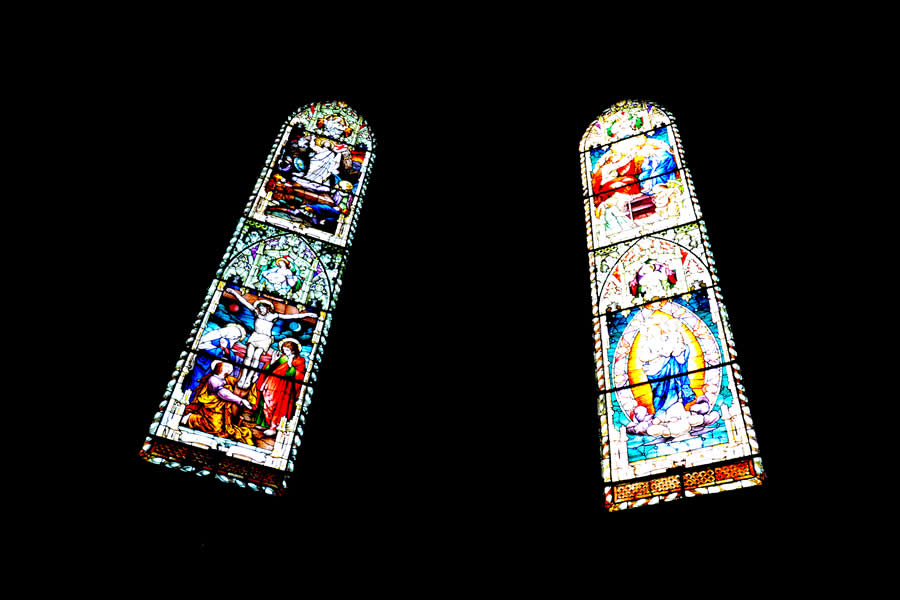

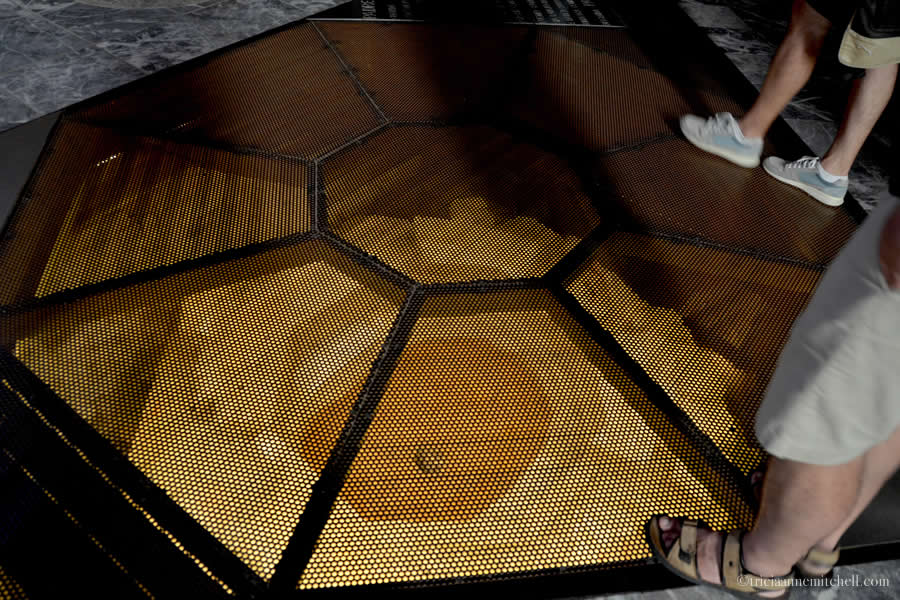

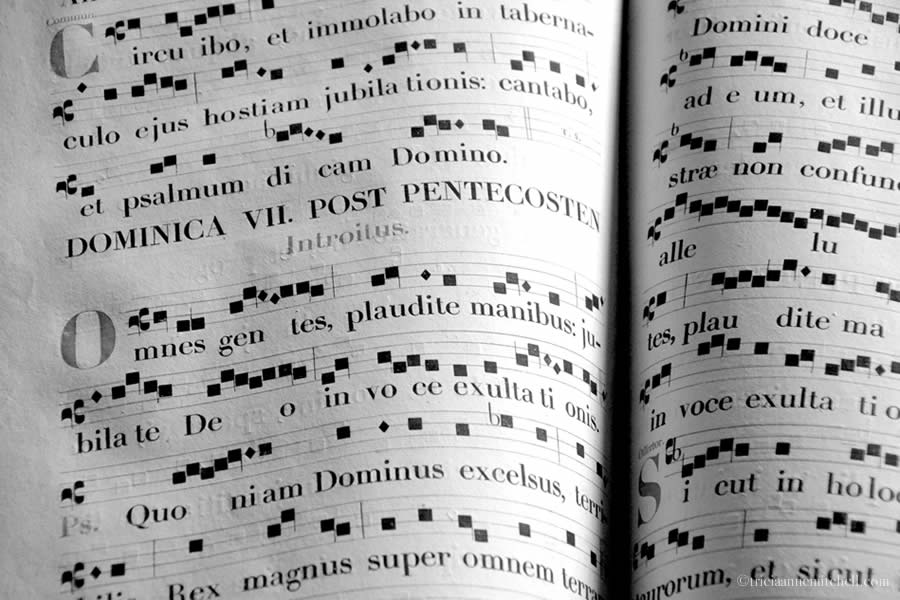

We would see other fixtures for which this capital city of the Langhe is known, mainly the Ferrero Chocolate Factory, and Alba’s elegant Neo-Gothic cathedral. We found it interesting to hear how the cathedral’s interior had evolved. Marco explained that the priest originally had his back turned to the congregation. Later, an evolving philosophy dictated that he face the attendees and be closer to them. This more recent evolution resulted in a new chandelier and altar being constructed. The light fixture is ultra-modern, and apparently stirred up quite a controversy when it was installed.

Video of This Experience:

Where in the World?

Planning Pointers:

- Italy’s Piedmont (Piemonte) region is located about 140 km (85 miles) southwest of Milan. High-speed trains link the Piedmont area to Italian tourist meccas such as Rome and Venice. See Trenitalia for schedules and prices.

- We traveled by train from Milan to Asti, and even day-tripped to Turin using Asti as our home-base for 3 out of 4 nights. In Asti, we stayed at the La Fabbrica dell’Oro Hotel (affiliate link). We found it to be clean and centrally-located, and we enjoyed our Palio-themed room, as well as all the black & white family photographs in the entryway. (The other night, we stayed at a lovely agriturismo in the Monferrato hills.)

- While we found mass transit accessibility to be good in larger Italian cities like Asti and Turin, we were told that public transportation is quite limited in Piemonte’s countryside. Locals routinely advised us to rent a car or hire a private driver.

- Marco, one of Meet Piemonte‘s co-founders, coordinated the details of our visit in advance, and guided us through each excursion. He and his colleagues lead customized tours covering everything from wine-tastings, to cooking classes, truffle hunts, hiking and biking excursions, and visits to Piedmont’s rice fields. Having worked in the tourism industry for more than a decade, Marco speaks fluent English and also helped ensure that tour partners took into account my gluten intolerance.

- For more information, visit the following sites:

- Need more inspiration? This link contains an index of all my posts from Italy.

Disclosure & Thanks:

Meet Piemonte hosted us during this day’s excursion.

We’d like to say Mille grazie to Marco for being such a knowledgeable, patient, and enthusiastic host.

Photography & text © Tricia A. Mitchell. All Rights Reserved. My husband, Shawn, created the video.

Join the conversation.