Arriving in what was to be our home away from home in rural Bulgaria, we knew not a soul. But by the time we left Kalofer, a tiny town tucked away in Central Bulgaria, where the livestock population quite possibly outnumbers the number of humans living there, an impromptu farewell committee was wishing us adieu.

As we rolled our bags out of town, over Kalofer’s bumpy roads spotted with droppings from the village’s numerous goat, cow, and horse residents, locals whom we’d not yet met popped their heads out over their fences exclaiming the equivalent of bon voyage in Bulgarian.

They waved goodbye, flashed wide smiles, and head bobbles that we’d determined to be customary in the region – gestures that are reminiscent of those we encountered in India.

Our time in Kalofer had not been planned. We’d discovered the town accidentally while looking for accommodations nearby in Bulgaria’s second-largest city of Plovdiv. Kalofer seemed to be appreciated among Bulgarians because of its proximity to Bulgaria’s famed lavender and rose-growing fields, its annual Lace Festival, its well-groomed eco-trails, its monastery and convent, and its status as the birthplace of several national heroes and revolutionaries. It was also regarded as a town awash with tradition – one that was even able to retain Bulgarian customs despite nearly five centuries of Ottoman rule.

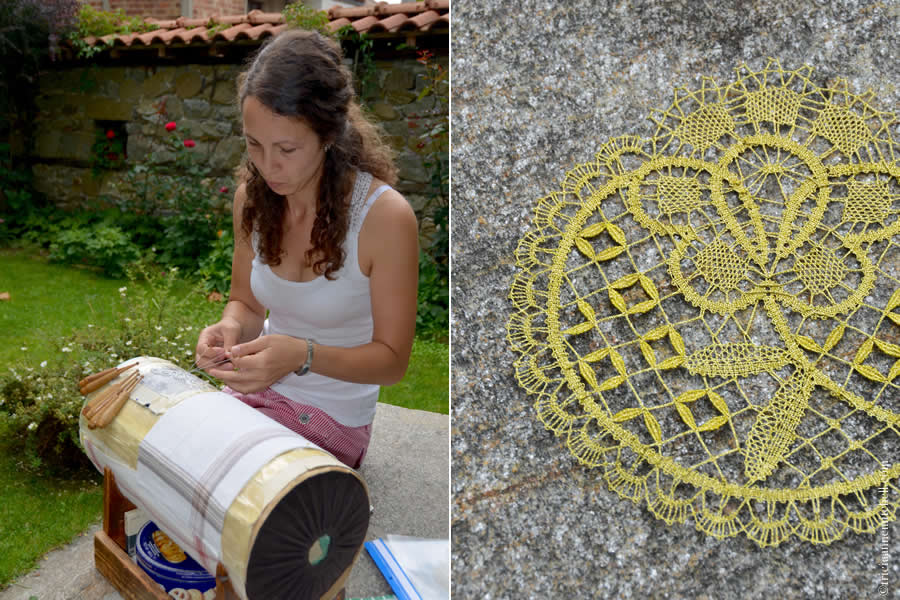

Shawn and I had been seeking somewhere ‘authentic’, a quiet place in which we could catch up on projects. Rural Kalofer, in the shadows of the Stara Planina mountain range, seemed to fit the bill. Little did we know then that its 3,000 or so residents would serendipitously show us all the Bulgarian culture that we had been seeking. From making homemade yogurt and watching the distilling of brandy, we learned much about Bulgarian cuisine. We also had the opportunity to soak up Bulgarian arts as women spun lace and young musicians played folk tunes on bagpipes.

Homemade Booties, Jam, & Brandy: The Kindness of Strangers

In Kalofer, we found ourselves touched by the generosity of strangers. Our guesthouse owners filled our arms with flowers and succulent, homegrown tomatoes. Market vendors tossed complimentary zucchini, mini peppers, and carrots into our bag after we’d made our weekly purchases. Several motorists even pulled their cars onto roadsides, to offer us rides when we were out for a walk.

Our first night in Kalofer, we took to the town’s sleepy residential streets, wanting to get a lay of the land and the town’s logistical offerings. We spotted a pair of cows wandering the streets solo, munching on goodies they’d unearthed in garbage cans.

“To my mind, the greatest reward and luxury of travel is to be able to experience everyday things as if for the first time, to be in a position in which almost nothing is so familiar it is taken for granted.”

Bill Bryson

Heading to a magasin (mini market), we encountered a group of four grandmothers, known as babas in Bulgarian. They were seated outside a brick home, some with canes in hand. They were gossiping, watching the livestock go by, waiting for the summer sun to slumber. We remarked that they’d likely known each other since childhood.

“Dobar den,” Shawn and I said, pulling out a pair of words we’d amassed from our scant Bulgarian-language arsenal. “Good day.”

At this, the grandmothers could not contain themselves. They waved their hands enthusiastically, and tossed out sentences chock-full of unknown Slavic words, as if we had native proficiency of Bulgarian. The granny whom we deemed to have the strongest personality waved her cane in the air to make her points, as her companions giggled. We privately nicknamed her the ‘Alpha Baba’.

As students of North American body language, we instinctively nodded our heads ‘yes’ and shook our heads side to side to signify ‘no’, even while remembering that Bulgarians do precisely the opposite. In Bulgaria, a side-to-side shake or head wobble signifies ‘yes’, while the up-down nod means ‘no.’ This made the conversation ever the more confusing and lighthearted, and all we could do was laugh. Even the Bulgarian grannies chuckled, causing the wooden bench on which they were sitting to shake.

We continued on to the diminutive market just down the dusty street from the babas. With its packed shelves and attendant behind the counter waiting to fulfill our order, the setting evoked images of American general stores of decades bygone. Delightful Pippa, whom we’d come to know over the coming weeks, was curious why we were in Kalofer, a destination that tends to attract more domestic visitors than international ones. She concluded that we must be students learning Bulgarian. From that moment on, she played the role of language instructor extraordinaire, teaching us how to order yogurt, milk, and white-brine cheese (kiselo mljako, mljako, and sirenje). The vocabulary for such staples as bell peppers and bread (chushkis and hleb) would come later.

As we headed back to our guesthouse, we saw a curious lady peering down at us from her second-story window. She had snow-white hair that was wispy, like a wand of cotton candy. We waved and exchanged smiles.

The next night, the same woman, whom we’d come to know as ‘Baba Maria’ or Grandmother Maria was sitting outside her neighbor’s gate, along the sidewalk on a hilly street. We still had just a smattering of words with which to communicate. Nevertheless, within seconds, we were smiling, laughing, and gesticulating. After half an hour of banter, Baba Maria and her neighbors were showering us with surprise gifts that were handcrafted and homemade.

First, came a pair of cream-colored wool slippers, lovingly made by Baba Maria. Baba Maria motioned for me to remove my sandals, and slip the woolen socks on. She looked pleased, but not perfectly content. As an expert seamstress I think she observed that they were just a tad too large.

With mischievous grins, her female neighbors then brought out a jar of homemade pear preserves, distinctly spiced with cloves. Next, Baba Maria instructed the ladies to snip off some of the fuchsia-colored Phlox flowers growing in their front yard, so that they could craft us a bouquet.

Touched by their kindness, but eager to sneak away before they bestowed more thoughtful trinkets upon us, we prepared to head home.

But there was more hospitality to be extended before we could escape. Baba Maria, who we learned to be in her early 80s, proudly presented us with a half-liter water bottle. With a twinkle in her eye, she exclaimed, “Rakija.”

Rakija is homemade moonshine, a brandy made with everything from plums, to grapes, and even walnuts. Having spent several months in the countries of the former Yugoslavia, we knew that Rakija could pack a powerful punch.

Baba Maria took off the plastic lid and encouraged us to take a sip. She carefully watched our expressions as we tossed the lids full of high-proof alcohol into our mouths. With our tongues on fire, we tried valiantly to flash the widest of grins.

“Dobro!” We smiled as we tried to fan the flames inside our mouths.

Baba Maria pointed to the bottle, then to herself. She wanted to be sure that we knew that she’d crafted the Rakija herself.

By the time we left Kalofer about five weeks later, Baba Maria, wanting to be sure I had slippers with the perfect fit, had made three more pairs for me. They ranged in hues from baby-pink and red, to winter white. Xristina, her neighbor with a penchant for making the delectable clove preserves, even knitted Shawn a pair of earthy brown socks that came up to his calf, thus ensuring his toes were warm in winters ahead.

Our hearts swelled from being the recipients of such generosity. And, suffice it to say that our mouths were ablaze at least once more when presented with a second bottle of Rakija from the ladies, followed by a third from our guesthouse hosts.

Some nights, we chatted with Baba Maria’s neighbors while watching the town’s dance troupe practice traditional Bulgarian steps. The men and women of all ages held hands as they twirled in a circle. Sometimes, they looked as though they were in deep concentration, making sure to get the fanciful footwork just right. But mostly, they laughed easily and smiled. Whenever we saw this practice, I always left with a warm feeling in my heart because of the lovely sense of community that we had just witnessed.

Another evening, we encountered a gentleman on a residential street. He saw that we were amused by his goats, which were nibbling on bushes cascading over a fence onto the sidewalk. He made a beeline for his pear trees, snipped off a few plump specimens, and handed them to us. We never saw him again, but we haven’t forgotten his thoughtful gesture, nor those flavorful pears.

Greeting Kalofer’s ‘Kids’ As They Come Home

A dispatch on Kalofer would not be complete without mentioning the daily goat processions. When we first arrived in town, we noticed goats walking unattended on the streets at sunset. Stopping at a home’s gate, they nudged it with their heads until someone answered it. We learned later that this ritual really was the ‘kids’ coming home.

Taken under the wing of new German-Bulgarian friends Elena and Poldi, we were invited to watch the evening goat procession. Together, on the outskirts of town, we met a cluster of goat owners who had gathered to greet their goats.

Each morning, Elena and Poldi explained, a Kalofer goatherder would collect his charges and take them out into the surrounding hillsides to graze. He was responsible for about 300 goats, and earned roughly 3 Lev (USD $1.75) as payment, per goat, per month.

As if there was a dust devil or impending tornado, the dirt soon swirled in the air as the hooves of several hundred goats hit the road. Amazingly, the goats were able to recognize their masters who had come to greet them. Those who didn’t have owners waiting for them, continued on to their respective homes. There, a nudge of a gate would signify to their owners that they were home, ready to come in for an evening feast.

After watching the goat procession, Elena and Poldi took us to their cousins’ home so that we could watch their goats being milked. The cousins, Elena and Xristo, told us that one goat could produce about a liter (roughly a quarter of a gallon) of milk a day.

Cousins Elena and Xristo then treated us to a feast of traditional Bulgarian fare: the ubiquitous Shopska Salad (diced cucumbers, tomatoes and white-brine cheese), a rice and pork dish, Banitsa (bread stuffed with cheese) and Lokum-filled pastries. The pièce de résistance was goat jerky flambée, which created a dramatic nighttime dish. Of course, Rakija and homemade wine also made prominent appearances at the table.

As the evening wore on, Cousin Elena sang songs attesting to Kalofer’s past as a rose-oil producing town. The lyrics described pretty petals and plump apples floating down the stream, and the perfume of roses in the air. Sadly, those factories have since closed, leaving Kalofer and much of Bulgaria still developing. However, the ladies’ heartfelt singing carried us back to a gentler time in Kalofer’s history.

Such acts of hospitality would continue, much due to the thoughtful introductions that our Bulgarian-German friends made to help us feel welcome in the community. We’d met Elena and Poldi because of their charismatic pooch, François, a boisterous French Bulldog. Following this sidewalk meeting, Elena and Poldi had swiftly invited us into their home to show off renovation projects. This mini tour was followed by an impromptu feast, and a sharing of photographs, while the dialogue was mostly in German. As the night wore on, a violent storm swept through the village, causing the electricity to go out for hours. This didn’t dampen the mood of our spontaneous feast; instead, Poldi used their laptop and candles to illuminate their dining room so that we could see each other’s faces.

We stayed at our new friends’ home until just after midnight, making the walk home on streets filled with branches disrupted by the powerful storm. On the way home, we also discovered that some of Kalofer’s loose dogs were not as hospitable – rather many were quite intimidating as they guarded the streets in front of their homes. On this night, I was so frightened by a pair of very vocal, aggressive dogs that I prepared to hop onto a vehicle for safety. Fortunately, Shawn was able to use his booming voice to keep the animals at bay. This incident made us happy that we’d had our rabies shots, and we vowed to never again stay out so late.

A Weaving Lesson & ‘The Rear Window’

Aside from daily goat and cow processions and free-roaming dogs, we also witnessed vignettes reminiscent of Alfred Hitchcock’s classic film, The Rear Window. Instead of being able to see the comings and goings of urban dwellers in New York City, we were regularly privy to the happenings in village residents’ homes.

Next door to our second guesthouse, for example, our balcony overlooked a backyard filled with chickens, two pigs, and a protective dog. We watched each morning as the household’s female resident put fresh helpings of food and water inside the pigs’ pen. She and her husband didn’t seem to have any interactions with the pigs, and when we saw meat hooks hanging on an adjacent support, we understood why. Though I do eat poultry and fish and I realize that it’s hypocritical for me to be sensitive about the prospect of seeing animals killed, I also felt thankful that we were not in that apartment when it came time to witness the slaughter of that pair of pigs.

Not long before our departure from Kalofer, we were invited to the home of Daniela, a former dental assistant eager to begin a weaving business specializing in making rugs featuring Kalofer’s traditional patterns.

Greeting us with a shot of Rakija and a dessert of candied plums in syrup, Daniela proudly showed us her newest acquisition – a wooden loom so massive that it consumed an entire room. Woodworm holes in the rich wood, paired with Daniela’s anecdotes, told us that this loom had an impressive history. Daniela said that she’d purchased it from Kalofer’s convent, and that it was likely 100 years old.

Daniela pointed out that her first carpet would take about two weeks to complete. Once she became more confident on the loom, however, she expected to be able to weave one carpet per week.

With our German-Bulgarian friends translating German into Bulgarian and vice versa, we answered Daniela’s questions about how to best market her creations. On a subsequent visit, Daniela, ever the gracious hostess, prepared a veritable smorgasbord of treats. Her selection included: a pudding dessert made from rice, milk, vanilla, cinnamon, and tender, steamed zucchini; Banitsa bread; and homemade jam produced with apples, apricots and plums from Daniela’s own garden.

As we said our farewells and walked out Daniela’s front door, she placed a tiny wooden vessel containing Bulgaria’s prized rose oil into my hands. It was wrapped in a decorative handkerchief that bore the image of a Bulgarian maiden in colorful dress, picking a basket of rose petals.

Time to Say Goodbye

After two wonderful months in Kalofer, it came time to bid farewell to the people that had treated us with such kindness and generosity. While sad to leave the tiny town, we were eager to explore more of the country. We’d already seen its capital, Sofia, and Plovdiv, but we also wanted to make stops in Veliko Turnovo, and two Black Sea cities.

En route to Kalofer’s bus stop on that last day, we were met by Elena and Poldi. Elena ran into her garden to gather a small bouquet of herbs as a farewell gesture.

“This is a tradition in Bulgaria,” she explained. Keep the bouquet watered in your train’s cabin, and beside your bed tonight at your new hotel. The herb will keep you calm and relaxed.”

Elena and Poldi were insistent about paying our bus fare to the train station, since they’d not been able to personally escort us there in their own car.

With sentimental memories of animals processions, and dinners illuminated by lightning or sizzling goat flambée now swirling in our minds, we bid farewell to our new friends and to Kalofer. At the train station, we would be greeted by a new trio of stray dogs, and within moments we were watching Kalofer’s lavender and sunflower-filled valley get smaller and smaller through a cabin window dressed with raindrops.

Kalofer and her residents had given us exactly what we had been seeking, and we hope we can someday repay their kindness to other international visitors.

Video of This Experience:

Where in the World?

Planning Pointers:

- Kalofer, a village of around 3,600 people, is located roughly 65 km. (38 miles) from Bulgaria’s second-largest city, Plovdiv. Local buses link the cities.

- We divided our time between the Iliikova House and Stara Planina Hotel (affiliate links). At the former, we enjoyed Tony and Stefan’s home’s stunning forest views, and pretty garden courtyard. The couple even took the time to show us how to make Bulgarian yogurt. At the latter guesthouse, we appreciated Stoyan’s and his family’s warm hospitality, and their willingness to introduce us to Kalofer residents who shared aspects of Bulgarian culture with us (lace-making and rakija-distilling). The family also shared a bounty of plump, home-grown tomatoes with us, which we joyfully included in the Shopska Salads that we feasted upon several times per week.

- Kalofer has an an ATM machine, as well as an assortment of small, family-owned grocery stores where you can purchase food and essentials. A friendly vendor also sells fresh fruit and vegetable at a single stand (near the bus stop) which we regularly frequented during the summer months. On Thursdays, there’s a larger outdoor market where multiple vendors offer produce, and homemade goods such as honey and liqueur. For a larger range of grocery-shopping options, we took a bus to Karlovo, a significantly larger town of about 25,000 people.

- For more details about Kalofer’s ecotrail, lodging options, and annual Lace Festival, see the village’s website.

- Since so many of the signs and written material are only written in the Cyrillic script, it’s helpful to acquire a basic understanding of it before you go. During long bus rides, I passed some of the time by sounding out road signs (some written in both Cyrillic script and the Latin alphabet) and this helped out later when we were stumped trying to decipher street signs or railroad time tables. :)

- Need more inspiration? This link contains an index of all my posts from Bulgaria.

Photography & text © Tricia A. Mitchell. All Rights Reserved. My husband, Shawn, created the video.

Join the conversation.